With hats it is, of course, useful to focus on the symbolic use of hats in Religion where it is evident they are developed consciously to serve a symbolic purpose. Possibly hats, as crowns and laurels, have a vaginal significance. Although here there is also a strong theme of concealment. To be clear, the two themes are not mutually exclusive. Quite the contrary, they are perhaps intrinsically linked.

We explicate this link, for example, with the symbol of the wooden ark, whether appearing with the baby Adonis, with the Ark of the Covenant or with Noah’s “Ark.” The symbol of the Ark, as this study explicates, is an Aryan vaginal symbol yet also a symbol, from the Jewish perspective, of racial camouflage or concealment. Here the element of wood signifies the Aryan element as this study explicates.

In the Religious context, the kippah, appearing in Judaism, and the taqiyah, appearing in Islam, are the most useful subjects of analysis. Here mitre’s or priestly hats appearing in Christianity are likely variations on a theme. This includes other symbols of “cover” such as the symbol of the umbraculum or “big umbrella”, a sunshade used to shade the pope during certain official ceremonies and appearing, as well, in papal iconography. This sunshade, like these aforementioned hats, is a symbol of “covering” and “concealment.”

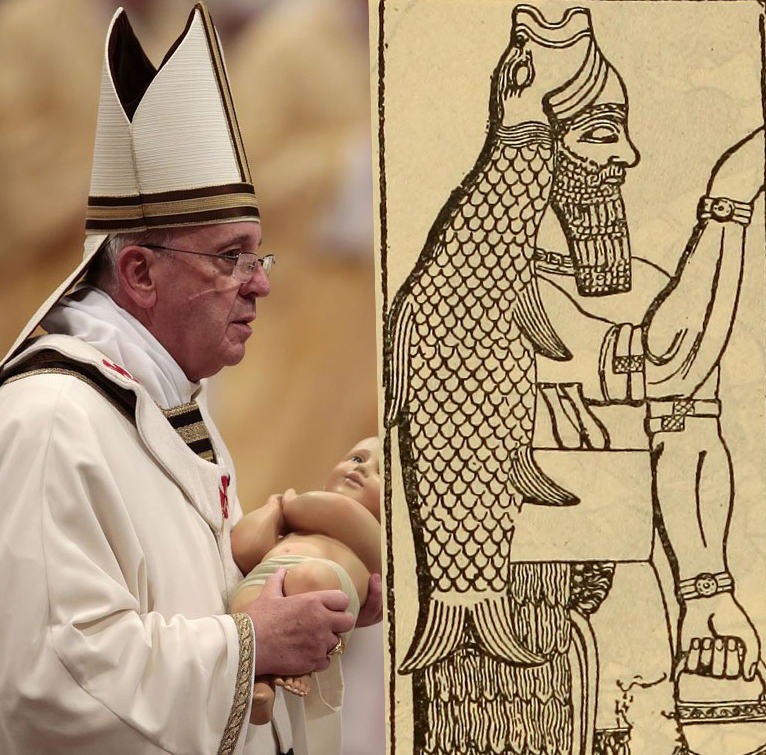

Indeed, the shape of the papal mitre was in its origin closer to a skullcap. The 19th century, anti- Catholic Protestant minister Alexander Hislop claimed that the papal mitre “is the very mitre worn by the priests of Dagon, the fish-god of the Philistines and Babylonians.” [1] Here, it is posited, the distinctive twin peaked shape of the modern mitre is taken from the ancient Dagon cult where a two peaked hat or headdress was developed, very explicitly, to represent the open mouth of a fish.

To be sure, some ancient depictions of this Dagon headgear more closely resemble the “beakish” mitre than others. Nevertheless, we shouldn’t consider the evolution of the mitre from another form to its present form disruptive of Hislop’s theory. After all, JEM, and an intelligent deployment of symbolism by Jews, has been active through all periods including our own.

Indeed, as this study explicates, the fresh water fish, river fish and Dagon, as symbols in JEM, signify the Aryan as consumable. This would seem, perhaps, consistent with other piscine symbolism that features saliently in papal symbolism such as, for example, the pope’s Piscatory Ring. Here the pope is understood as the spiritual heir of Peter and “the Fisher of Men.”

If Hislop’s connection is the correct one, ostensibly, this would assign the mitre a different meaning than the kippah or taqiyah. But ultimately this is actually untrue. Indeed, it seems likely the hat in the Religious context carries an inherent symbolism of concealment, inhabitation and even phallic insertion.

It may or may not be meaningful, for example, that the Greek word mitra, μίτρα, from which mitre is derived, originally described a piece of hoplite armor worn around the waist. In any case, even if we guess the mitre contains piscine symbolism, the pope or bishops as “fishers of men,” don’t become Aryan piscine figures through wearing these hats. Rather they disguise themselves as Aryan piscine figures.

Perhaps, straightaway, the knowledgeable reader is drawn to the word taqiyah, طاقية. The word taqiyah, spelled also tagyia in English, is strikingly similar to the word, taqiya, تقیة. Here we can be sure there is no “etymological coincidence” and word meanings tend to corroborate this.

In Islam, the principle of taqiya is the practice of concealing one’s faith and, implicitly, a clear understanding of it, when facing “Religious Persecution.” Hence, very clearly, we understand the cap of essentially the same name to represent a concept of concealment. Here one is hiding beneath a cap, particularly from higher, celestial or ruling native powers, residing “above.”

The taqiyah is a skullcap doubtlessly imitative of the Jewish kippah. It is derived from the Persian word ṭāq, طاق, meaning “dome” or “arch.” The kippah, כִּפָּה/כִּיפָּה, likewise is indicated as meaning “dome” or “arch.” Kippah also means “skull cap”, “cap”, “cupola”, “vault”, “knoll” and “palm.” Since we assume a Jewish hand or influence in the development of the key symbols of Islam, doubtlessly the corresponding Jewish kippah is likewise a symbol of crypsis. This is corroborated by the ubiquitous theme of crypsis in JEM.

To be sure, both the kippah and the taqiyah are posited exoterically as symbols of “humility” or “fear of God.” Indeed, the term yarmulke, a Yiddish word for kippah, is frequently felt to have been derived from the Aramaic phrase yare malka, ירא מלכא, meaning “fear the King.” “King” here is sometimes guessed to be a reference to the Jewish God. Though it seems as likely this “king” refers to the Aryan or non-Jewish potentate. After all, we understand the Jew believes himself esoterically as Yahweh as this study explicates.

In Arabic, the practice of taqiya means literally “prudence, fear.” Indeed, the kippah and taqiyah also appear, exoterically, as symbols of “humility.” Of course, a calculated, even temporary humility is merely another form of dissimulation or concealment. Hence these skullcaps are symbols of “false humility” in addition to dissimulation.

There are many striking things to consider here. With meanings like “dome”, “arch” and “knoll” appearing with the word kippah, we are given a sense of the chthonic. Here we find a mountain God, Yahweh, concealed, even underground, hiding from an Aryan Sky God above. Indeed, the hat, designed to protect from weather conditions, by itself, in the religious context, suggests a desire to conceal oneself from the judgment of Celestial Gods or forces.

With the meaning of “palm,” found with the word kippah, it seems plausible we see a reference to the open-palmed Hamsa, a symbol explicated in this study. Here it is just worth mentioning that the Hamsa is a symbol of blinding, blocking, concealment and theft, particularly genetic theft. In Islam, the taqiyah is worn especially during the “five daily prayers.” In JEM, the number five, as this study explicates, is especially a reference to the five fingers of the Hamsa and a theme of blinding or deception.

Hence with a kippah or taqiyah the most amazing irony appears. Doubtlessly it was developed intentionally. Donning one of these caps publicly is obviously an announcement of faith. Yet both are symbols of the concealment of faith or at least the concealment of mission. Here again JEM is heightened because one is announcing to their adversary that they are deceiving them, yet their adversary is too incurious, ignorant, terrified or dim-witted to understand.

Hats and caps have a long religious history appearing in various ancient cults. Here, though, particularly when knowledge of ritual practice and garb is finite, it is useful to look at mythical figures. After all, these mythical figures may be understood as the most imitable models of their given cults particularly vis-à-vis priests. Indeed, in my estimation, it is clear that kippah is related to the pileus, a common traveling hat, associated with the mythical twin figures of the Dioskouroi.

The Cabeiri, from which the Dioskouri almost certainly derive, appeared first in Lemnos. Lemnos was unequivocally a site of proto-Jewish inhabitation as this study explicates. Indeed, the Cabeiri themselves were an offshoot of the proto-Jewish Vulcan cult indigenous to Lemnos. In fact, Vulcan himself is commonly depicted with a beard and an oval cap. It is a cap often bearing a striking resemblance to the kippah.

The Phrygian cap, a typically larger pointed hat, is likely also related. In antiquity the Phrygian cap is depicted on the heads of the chthonic and Semitic figures of Eros and Orpheus. Both the pileus and Phrygian cap were understood as symbols of liberty and emancipation from slavery. The Semitic figure of Mercury likewise wore a “traveling hat” with a broad, floppy brim called the petasos. We can be sure it is the inspiration for the wizard’s hat of European folklore. Indeed, Mercury himself is the inspiration for the wizard. The name Merlin, for instance, may be derived from the name Mercury.

With the Semitic figures of Mercury and Pluto, we also understand hats or helmets as symbols of invisibility or, to be clear, Jewish or proto-Jewish crypsis. The mythical figures Pluto and Mercury both had helms or caps of invisibility. In modern JEM, the Ant-man character of Marvel comics, developed by Stan Lee, requires a special helmet to shrink down to insect size. This ability to shrink is certainly a reference to crypsis.

In Western culture, it was, in the past, customary to doff the hat when indoors. It was also once customary, as well, to tip the hat upon encountering a woman. Both gestures, little considered, are ultimately gestures of revealing, of forthrightness, of baring one’s face.

The difficult truth is nothing demonstrates the principal of “Opaque Symbols as ipso facto demoralization” more than the kippah, which is itself a symbol of concealment, deception, hidden and ulterior motives. Hence, as a straight dealing people, interested only in other straight dealing people, there are few things we should regard as more offensive than the kippah. Though let us remember as well, few Jews are aware of the meanings I explicate here.

[1] The Two Babylons, Hislop, p. 215

The hat is something I’ve noticed as well. In modern times I believe it’s been reflected in both the pussy hats and the MAGA hat. Implying symbolic control on both sides of the political split.

LikeLike

That’s a remarkable observation. In a sense, both hats, as in the ancient world, are symbols of liberty or emancipation. It appears to be a Jungian manifestation at least on the right. Though there is no hat more clearly vaginal than the “pussy hat.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

How would you interpret the putting on of the kippa by US and other presidents when visiting the wailing wall in that context?

LikeLike